Famous People

BEETHOVEN: IN A MAJOR AND MINOR MOOD

BEETHOVEN: IN A MAJOR AND MINOR MOOD

His life could fill up a segment on Oprah.

by John McManamy

His life could fill up a segment on Oprah.

by John McManamy

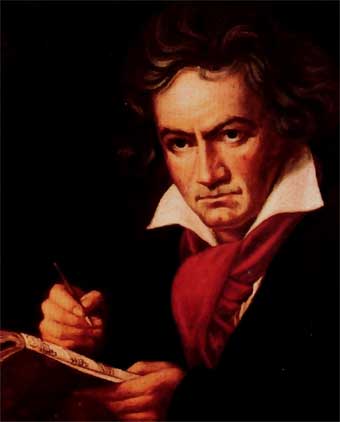

No one had ever heard music anything like it before. It soared, it flew, it triumphed against all natural laws, all while struggling against itself in a way that suggested no possible resolution. On one hand, he remained true to the classicism of Mozart and Haydn, on the other the sheer power and passion of his work broke the mold forever.

Say hello to Ludwig van Beethoven, the most influential composer of all time.

We know him best, of course, by his Choral Symphony, but the Beethoven aficionadi have their own favorites: The Seventh Symphony, the Emperor Concerto, the Waldstein Sonata, the later string quartets ...

There's no right or wrong choice, here. Sometimes, it can be a Beethoven moment as opposed to a whole piece: the coda in the Egmont Overture, the stormy intro to his Eroica Symphony, the trombones barking out their lofty challenge in the last movement of the Fifth Symphony.

His life could fill up a segment on Oprah: an abusive father who tried to exploit him as a child prodigy, an infatuation for women who were totally out of reach, a tragic deafness that defies imagination, the comical frequency in which he shifted residences in Vienna, his disillusionment with Napoleon, his unkempt appearance and lack of personal hygiene, a man with a vision of universal brotherhood increasingly withdrawing into himself.

It's almost tempting to stop right there, as if his tormented life were reason enough to explain his exalted music, but the written record demands a closer look. Beethoven wrote a lot of letters and so did his friends, and in their 1999 book, "Manic Depression and Creativity," authors D Jablow Hershman and Dr Julian Lieb argue quite convincingly that the great composer lived with bipolar:

"I joyfully hasten to meet death," Beethoven wrote as his deafness made itself apparent, "... for will it not deliver me from endless suffering?"

This was no isolated event. An 1801 letter to a friend refers to a two-year-long depression. The next year he is begging Providence for "but one more day of pure joy." In 1813, he may have attempted suicide, disappearing and being found three days later. In 1816, he wrote: "During the last six weeks my health has been so shaky, so that I often think of death, but without fear ..."

Ironically, his bipolar may have enabled him to survive deafness and loneliness. According to the book's authors:

[Bipolars] can be happy without cause, or even in the face of misfortune It may be that Beethoven survived as a creator because he was brave or because his love of music kept him going. What he did have were his manic days of "pure joy" that he prayed for, and manias triggered by the process of working, along with the confidence and optimism mania brings.

SIGN UP FOR MY FREE EMAIL NEWSLETTER

His mania seemed to stoke his creativity, as he crashed and banged on his pianoforte, taking the instrument to its limits, scribbling on walls and shutters if paper wasn't available, dousing his head with water that ran through to the rooms below.

A friend describes one Beethoven session:

He ... tore open the pianoforte ... and began to improvise marvelously ... The hours went by, but Beethoven improvised on. Supper, which he had purported to eat with us, was served, but - he would not permit himself to be disturbed.

His mania also had its flip side, as relationships fell by the wayside in the wake of raging quarrels and psychotic delusions. On one occasion, he flung a gravy-laden platter of food at a waiter's head. His friends called him "half crazy," and when enraged, "he became like a wild animal."

Ultimately, Beethoven medicated himself with the only available drug besides opium - alcohol. He literally drank himself to death. And as deafness closed in around him, he withdrew from the world, into himself. He wrote his Eighth Symphony in 1812. Then his creative output dried up. In 1824, he would premier his Choral Symphony. It was as if a piece of this magnitude required a tortuous 12-year gestation. He would also compose his transcendent string quartets. But soon his liver would give out on him, and in early 1827 he died at the age of 56, leaving behind sketches of a tenth symphony the world would never hear.

The authors of "Manic Depression and Creativity" note a rough correlation between Beethoven's manic phases and his creative bursts. Apparently, winter depressions stopped him in his tracks while summers brought on periods of intense activity. As a friend noted: "He composes, or was unable to compose, according to the moods of happiness, vexation or sorrow."

The authors of "Manic Depression and Creativity" note a rough correlation between Beethoven's manic phases and his creative bursts. Apparently, winter depressions stopped him in his tracks while summers brought on periods of intense activity. As a friend noted: "He composes, or was unable to compose, according to the moods of happiness, vexation or sorrow."

But as to whether manic depression actually constituted the creative spark in Beethoven, the authors defer to none other than Beethoven's teacher and fellow composer, Franz Joseph Haydn:

You will accomplish more than has ever been accomplished," wrote Haydn at the beginning of Beethoven's career, "have thoughts that no other has had. You will never sacrifice a beautiful idea to a tyrannical rule, and in that you will be right. But you will sacrifice your rules to your moods, for you seem to me to be a man of many heads and hearts. One will always find something irregular in your compositions, things of beauty, but rather dark and strange.

First published 2000, reviewed Jan 7. 2017.

NEW!

Follow me on the road. Check out my New Heart, New Start blog.