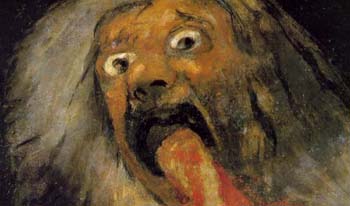

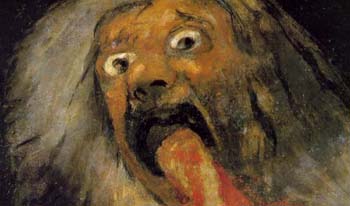

Mood

PSYCHOSIS IN MANIA

PSYCHOSIS IN MANIA

Knowing how to keep cool can help you stay calm.

by John McManamy

Knowing how to keep cool can help you stay calm.

by John McManamy

IN MY book, NOT JUST UP AND DOWN, I report …

Back in 2012, I drove across town to hear Maricela Estrada give a talk hosted by the International Bipolar Foundation. A couple of years earlier, she had self-published a book, Bipolar Girl: My Psychotic Self.

I arrived early and thus had a chance to have a one-on-one conversation. Maricela is in her early 30s and is employed as a medical case worker for the Department of Mental Health in LA. She has an engaging manner and a delightfully bubbly personality, and in no time we were laughing and joking.

She experienced her first episode as a school girl and has survived numerous suicide attempts, not to mention a drive-by shooting where a bullet whizzed past her head as she was lying in bed. The depressions continued through high school, but could not extinguish her irrepressible high spirits. She was very popular as a student, involved in activities, and elected prom queen.

Things fell apart soon after graduation. Mania, psychotic breaks, more suicide attempts, hospitalizations. During stable periods she managed to hold down various jobs and excel in college. But then she would go off her meds and things would unravel.

One time, in a car in a parking lot, she was convinced the world was ending. She heard a chorus of angels. She started screaming at people, and stripped off her blouse in order to be as naked as Adam and Eve. She was apprehended and handcuffed and put into a police car, breasts exposed.

In due course Maricela ended her denial and accepted the fact that she needed to stay on her meds. The meds were no picnic, but eventually she found a regimen she could tolerate

What is Going On

In case you’re wondering, psychosis is about as bad as it gets. Even in severe mania, one can argue, we can at least discern a tenuous connection to reality. In psychosis, we get the impression of the mind breaking free of reality’s gravitational field. The condition may exist as a stand-alone entity, but it is most associated with schizophrenia, where it is a core feature. In the context of mood disorders, we get the impression it is hitching a ride on depression and mania.Back in the old days, psychosis was virtually interchangeable with “insanity.” These days, we identify the term with hallucinations and delusional thinking. In some cases, we may see a breakdown in personal identity.

Now that I’ve scared the crap out of you, it is perfectly normal to feel a sense of disorientation a good deal of the time. Our neural circuits hardly process simultaneous sensory information at the same uniform speed, much less to the same level of completion. Our brain, to compensate, is constantly filling in the blanks, adjusting, anticipating, often seeing and hearing what is not there. Just one example: The “blind spot” of the retina contains no photoreceptors. The brain literally Photoshops a more complete picture. What we “see” is only a representation of what we think we see.

SIGN UP FOR MY FREE EMAIL NEWSLETTER

On top of that, we are screening this information through the complex filter of our own fears and desires and cognitive biases. Basically, we have constructed a working reality that gets us through the day. It’s how the healthy brain works. But it would be a mistake to view this as an objective bitmap reproduction of our environment.

Seen this way, it is easy to see how distortions in one’s personal reality may develop. It’s happened to all of us—our food takes on an unaccountable metallic tang, we swear we hear people talking, and so on. Then reality—our personalized version—resets to normal and we think no more of it.

The Center Cannot Hold

But imagine if things go wrong.

In her highly acclaimed 2007 book, The Center Cannot Hold, Elyn Saks recounts how as a graduate student at Oxford she caught herself talking to herself on the street and didn’t regard this as strange. Things went downhill from there. Nevertheless, with professional help, she managed to hold herself together and complete her degree, taking four years instead of two. Dr Saks was diagnosed with schizophrenia, but it took her a full two decades to reach a state of acceptance. As she wrote in a January 23, 2013 op-ed piece in the New York Times:

My prognosis was “grave”: I would never live independently, hold a job, find a loving partner, get married. My home would be a board-and-care facility, my days spent watching TV in a day room with other people debilitated by mental illness. I would work at menial jobs when my symptoms were quiet.

Today, she is a chaired professor of law at USC, plus an adjunct in psychiatry at UCSD, plus is on the faculty of the New Center for Psychoanalysis in LA, and is married. In her book, she described her first romantic kiss in lord knows when. “It was fantastic,” she wrote. “It was even better than getting an article published.”

Historical Background

In 1899, Emil Kraepelin, the father of diagnostic psychiatry, brought order to psychiatry by separating out manic-depression from what he called “dementia praecox,” which he viewed as an irreversible cognitive disintegration. His followers changed the name to schizophrenia to imply a better prognosis.

In his 1921 Manic-Depressive Insanity, Kraepelin noted that delusions may occur in mania, “usually in a more jocular way.” This accords with the modern conception of “mood-congruent” features, such as seeing oneself as descended from royalty. Delusions congruent with depression, on the other hand, “frequently exist in the closest connection with the delusion of sin.”

Psychiatrists in Europe and America readily adopted Kraepelin’s manic-depression/schizophrenia split, though not always in ways the old master would have imagined, and the early DSMs did little to instill diagnostic confidence. One problem involved patients who seemed to fall into the so-called gap between manic-depression and schizophrenia.

The DSMs I and II categorized “schizoaffective” as a “type” of schizophrenia. The DSM III upgraded the condition to a “disorder,” profusely apologized for lack of a checklist, and simply urged clinicians to make the diagnosis when they couldn’t decide between a mood disorder or schizophrenia. This is how clinicians still operate for the most part.

If the patient happens to be African-American, by the way, one guess what doctors decide. Please, don’t make me cite the studies.

As a rough guide, on one side of the divide, we have DSM acknowledgement that psychotic features can occur in bipolar mania and depression and in unipolar depression. The understanding is that the psychosis is part and parcel of the mood episode. In other words, in bipolar, where there is no mood episode there should be no psychosis.

The implication is you can manage psychosis by managing your moods.

Over on the other side, we have acknowledgement that mood episodes may exist in schizophrenia, but these are a sideshow compared to the main event of disordered thinking and behavior. Psychosis is viewed as part and parcel of a major cognitive malfunction rather than bearing any relation to mood. Clinicians tend to look for delusions of the more bizarre variety, “incongruent” with mood.

Also, compared to the more fleeting psychoses associated with bipolar, delusions in schizophrenia may go on for years on end.

So far, so good. As to what lies in the middle …

The DSM appears to view schizoaffective as a hybrid, one that incorporates “schizophrenia lite” combined with bipolar I. The disordered thinking and behavior associated with schizophrenia are evident, but not with the same severity and duration. Clinicians also look for evidence of psychosis occurring without the mood episode. In effect, the psychosis is free-floating.

All well and good, but everything breaks down in the real world. Just a slight alteration in presentation from one psychiatric visit to the next can change the diagnosis. Indeed, the schizoaffective diagnosis simply doesn’t hold steady over the course of a lifetime.

Back to the Present

Maricela is the story of a woman who has fallen down seven times and picked herself up eight. Dr Saks battled against an inhumane mental health system that was all too happy to write her off. Both are doing very well. Both have found meds that work for them.

But deep in our gut we also know that the battle is never over. One snap of a thread, one straw too many, one prank of a trickster god—then things fall apart. The center cannot hold. With recovery, as with life, there are no happy endings, only an endless succession of beginnings, each with their special terms and conditions, each with their new sets of demands.

We have picked ourselves up more times than we have fallen, but what about next time? We are a walking mass of contradictions—strong and courageous and resourceful, but also vulnerable. That is one of the lessons we can all learn from listening to people like Maricela and Dr Saks. We can cheer their considerable triumphs, but at the same time we are holding our collective breath

See also: Schizoaffective Disorder.

New article, June 19, 2016

NEW!

Follow me on the road. Check out my New Heart, New Start blog.