Famous People

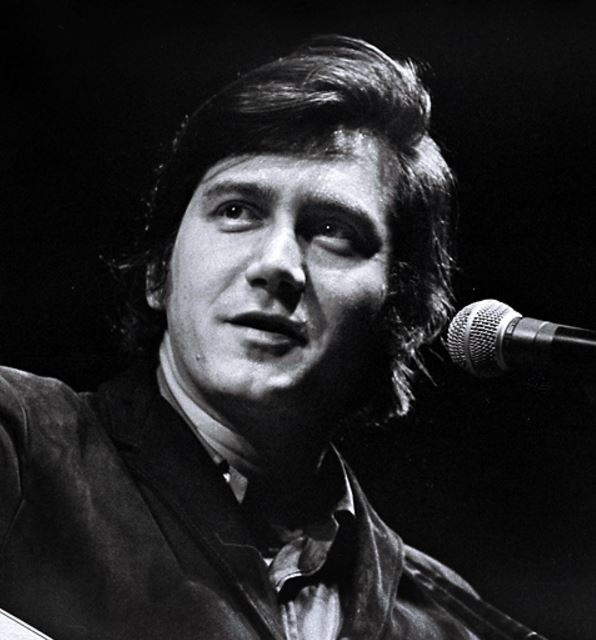

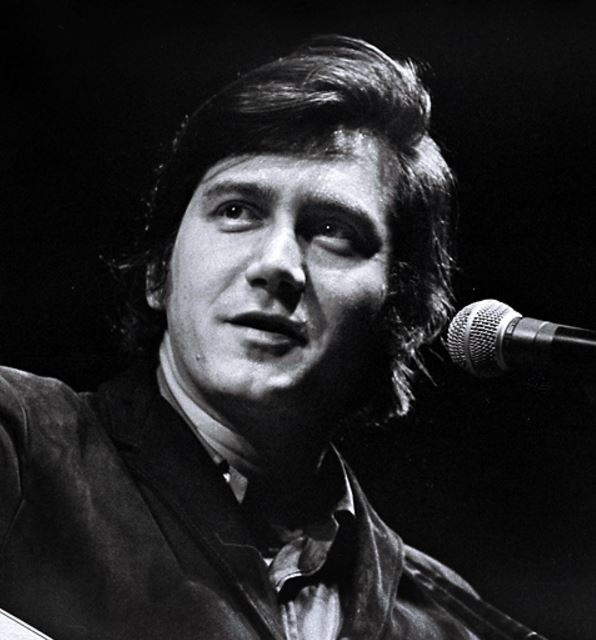

PHIL OCHS: AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY

PHIL OCHS: AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY

The 60s did not end as anyone imagined. But Phil took it personally.

by John McManamy

The 60s did not end as anyone imagined. But Phil took it personally.

by John McManamy

TWO OR THREE hundred years from now, when historians look back on the events that set in motion America's fall from preeminence, they are certain to take a very close look at the 1960s. You can almost split that decade right down the middle - hope and promise on one side, cynicism and disillusionment on the other.

Phil Ochs is probably the most influential folk singer/political activist most of you never heard of. His life was an expression of that pivotal decade, lovingly yet unsentimentally captured on film in the form of a 2010 documentary film by Ken Bowser, "Phil Ochs: There but for Fortune," released as a DVD in 2011.

In 1962, Phil Ochs, fresh out of Ohio, arrived on the Greenwich Village folk music scene when it was in full flower. Kennedy had been in office for a year, and his New Frontier held out the promise of the full unlocking of human potential. Whatever wrongs there were in the world could be righted. It was a new day.

The optimism of the era was a good fit for the ethos of "American exceptionalism," the idea that the country's children and children's children were special people leading the world toward a new destiny. Archetypal cinema heroes such as John Wayne and Gary Cooper apotheosized that myth, and even rebel antiheroes such as James Dean and Elvis could neatly be folded into it.

So here was Phil Ochs, young man with a guitar, brought up on the American Dream, out to change the world. Very quickly, he found his voice as a singing journalist, performing his own wry musical commentaries on the events of the day, part of a scene that included Pete Seeger, Peter, Paul, and Mary, and Bob Dylan. His first album, in 1964 for Elektra Records, was titled, "All the News That's Fit to Sing."

But whereas Dylan was producing campfire music such as "Blowin' in the Wind," Ochs' songs were evocative of the labor movement, the type of stuff you listened to as the police and company goons gratuitously battered your head to pulp. This from "The Ballad of Medgar Evers":

In the state of Mississippi many years ago

A boy of 14 years got a taste of southern law

He saw his friend a hanging and his color was his crime

And the blood upon his jacket left a brand upon his mind

Dylan and Ochs initially had a friendly rivalry going. Indeed, Ochs aspired to be a Dylan, but the only way to do that would have been to pen his own "Blowin' in the Wind." Instead:

The killer waited by his home hidden by the night

As Evers stepped out from his car into the rifle sight

he slowly squeezed the trigger, the bullet left his side

It struck the heart of every man when Evers fell and died.

Joan Baez managed to turn one of his songs, "There but for Fortune," into a minor hit. The song asked us to identify with the downtrodden, but empathy is a very heavy psychological burdern. As Richard O'Connor in "Undoing Depression" remarked:

I can't help thinking that part of the reason was the pain his vision cost him - the pain of putting yourself in the place of the "other guy," of not allowing yourself to feel safe and superior to a faceless, anonymous other, but knowing except for a few lucky breaks you might be in that position yourself.

Although mass market success eluded Ochs, he was at the epicenter of a movement that deeply resonates five decades later. But that age was coming to a close. First came the assassination of Kennedy. Then Kennedy's successor, LBJ, stepped up US military involvement in Vietnam. Suddenly, everyone was writing protest songs.

Phil and his guitar were everywhere, at music gigs, at folk festivals, at political protests. Again, change was possible, but this time it was more like pushing a rock uphill. No one seemed to be paying attention. The Vietnam War escalated. Pent-up racial frustrations erupted on the streets. King was assassinated. RFK was assassinated. Too many martyrs. Political opinion polarized and hardened. Hatred ruled. The protest movement fragmented and headed off on its course of self-destruction.

SIGN UP FOR MY FREE EMAIL NEWSLETTER

Ochs was one of the organizers of the protests of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, held in Chicago. Mayor Richard Daley, with obvious collaboration from the federal government, refused to issue permits for the protests. Instead, he met the protesters with brutal force, what a government commission later declared to be a "police riot."

The convention nominated Hubert Humphrey, now seen to be LBJ's lackey. This opened the way for the election of Richard Nixon, who cynically exploited right-wing resentment over civil rights and hippies.

The die was cast: The government in effect had issued an edict that it would listen to neither reason nor to its own people. The monied interests had always run things, but now no one was even pretending to believe otherwise.

As "There but for Fortune" makes loud and clear, Phil took all this far more personally than everyone else. The cover to Och's 1969 album, "Rehearsals for Retirement," says it all. We see his own tombstone, announcing his death in Chicago, 1968.

Earlier, Ochs had relocated to LA, where he signed with A&M records. The old folk scene was dead and Phil wanted to try something new. His songs grew more personal and introspective, but the over-orchestrated arrangements did him a horrible disservice. Indeed, all these years later, these recordings are excruciatingly painful to listen to.

The critics predictably panned these albums, but Phil entertained the delusion - almost to the end - that each new recording would bring him stardom. By now, his drinking was out of control and his moods were swinging wildly (his father had been hospitalized for manic-depression).

Phil was still involved with the anti-war movement, but it was as if he were walking in his sleep, with occasional bursts of coming alive. In 1971, he visited Chile, which had recently elected a Marxist government headed up by Salvatore Allende. There, he made friends with folk singer Victor Jara. Two years later, Allende was overthrown and killed in a right-wing military coup. Jara was publicly tortured and brutally murdered.

By now, Phil was a broken man, in spirit and in mind. A mugging in Tanzania left him with damaged vocal chords. He took on the identity of John Butler Train, declaring that he - John Butler Train - had murdered Phil Ochs. The last we see of Ochs on film is him on the streets, disheveled, in a psychotic trance, eye movements and body movements disconnected, rambling incoherently.

Phil Ochs did make one last return, but this time as a deeply depressed shell of a man who could not venture off the couch at his sister's place in Long Island. He only had the energy to hang himself. He was 36.

So, back to the future. America is a second-rate power. How did it happen? What precipitated the decline and the subsequent Age of Darkness? Who knows? But cast your mind back to the sixties. Focus on one man, an historical footnote but very much someone who embodied that turbulent era. Look closely. What was his state of mind at the beginning of that decade? What was his state of mind at the end?

One bright shining moment extinguished. An American tragedy.

First published as a blog Sept 9, 2011, republished as an article Sept 15, 2011, reviewed Jan 5, 2017.

NEW!

Follow me on the road. Check out my New Heart, New Start blog.